Why Causality Matters for Health Equity: Understanding Path-Specific Fairness

- Oct 2, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 9

Statistical Methods at DSxHE: Blog Series on Methods for Health Equity

The Statistical Methods section of Data Science for Health Equity (DSxHE) is launching a public-facing blog series that demystifies methods and showcases their real-world impact on health equity. Each post will blend clear, accessible explanation with concrete applications, from study design and causal inference to measurement, modelling, and evaluation, highlighting how methods can drive fairer health outcomes. We invite authors to bring not only their technical expertise but also their personal insights, and encourage anyone interested to volunteer their perspective. Submissions can be tutorials, case studies, opinion articles, or "what we learned" stories.

Want to contribute? Send a brief pitch or draft to info@datascienceforhealthequity.com.

Editorial note: Posts in this series are written by volunteers. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of Data Science for Health Equity (DSxHE).

When ‘Fair’ Isn’t Really Fair: Causality-Blind Health Equity Pitfalls

In health care, ‘fairness’ is often reduced to equal access or equal treatment. But this ignores how structural inequities shape patient outcomes.

Imagine you’re a large healthcare provider. To use limited resources wisely, like preventative care programs or referrals to specialists, you rely on an algorithm to predict which patients are most at risk of serious health issues in the coming year. This algorithm considers a variety of factors: patients’ age and chronic conditions, their past healthcare spending, and even their race. The spending might appear to serve as a “neutral” measure, reflecting how severe someone’s conditions have been and how much care they’ve needed over time. But what if the data itself reflects past inequalities? This is where typical ideas of fairness can fall short. We need to think causally, not just associatively.

Through my doctoral studies, I’ve become especially interested in how causal methods can move us beyond surface-level associations. By focusing on the “why” behind patterns in data, we can make more accurate predictions of patient outcomes and design decisions that promote equity rather than reinforce disparities. To illustrate, let me walk through a real example that shows how surface-level fairness can reinforce inequities.

A Simple Example: Race, Spending, and Predicted Risk.

Let’s break this down with a scenario that was actually encountered in the US healthcare system a few years ago:

A: Race (A=1 for “Minority Race”, A=0 for “Majority Race”)

M: Past Healthcare Expenditure (High or Low)

Y: Predicted Risk of Severe Health Complication

In this example, on average, patients from the minority racial group (A=1) tended to have lower recorded healthcare spending. This does not mean they are healthier. They face systemic barriers such as unequal treatment, delayed diagnoses, less aggressive care, or living in under-resourced areas. When the algorithm learns from this historical data, it might observe that patients with low past spending (M=0) generally have lower risk (Y). However, this pattern is misleading. It is affected by the fact that spending itself is influenced by race through systemic inequities.

The Pitfall of “Fair” by Association

An “associative” fairness test might check whether, for a given level of spending, the predicted risk is similar across racial groups, e.g., is P(Y | M, A) roughly equal for A=0 and A=1? If yes, it seems fair! But this ignores the discriminative reasons behind the spending variable.

If past spending (M) is biased, meaning it’s lower for some racial groups because of discrimination or structural inequities, then an algorithm that uses M naively can perpetuate that bias.

The Causal Fairness Lens: Paths that Matter

Causal fairness asks: Through which pathways does a protected attribute (like race) affect the prediction? Which of these paths are acceptable?

In this example:

A direct effect: Race directly affects the predicted risk.

An indirect effect: Race affects past expenditure, which in turn affects predicted risk.

When expenditure is itself unfairly lowered by systemic barriers, the indirect path

A → M → Y is also discriminatory.

Counterfactual Thinking: Natural Direct and Indirect Effects

To see this, we can ask a counterfactual question: “Would this minority patient’s predicted risk be higher if they had the level of past healthcare spending they would have had if they’d been from the majority group, even if their race stayed the same?”

This idea of using counterfactuals, comparing outcomes under different scenarios that could have happened, is the basis of causal fairness analysis.

The Natural Direct Effect (NDE) measures the part of the effect that goes directly from race to risk, holding the mediator (spending) constant at what it would have been for the other group.

$$\text{NDE}=\mathbb{E}[Y(A=1,M(A=0))]−\mathbb{E}[Y(A=0,M(A=0))]$$

The Natural Indirect Effect (NIE) captures how much of the effect flows through the spending variable.

$$\text{NIE}=\mathbb{E}[Y(A=0,M(A=1))]−\mathbb{E}[Y(A=0,M(A=0))]$$

If either effect is non-zero due to unfair systemic bias, we have reason to flag the algorithm as discriminatory.

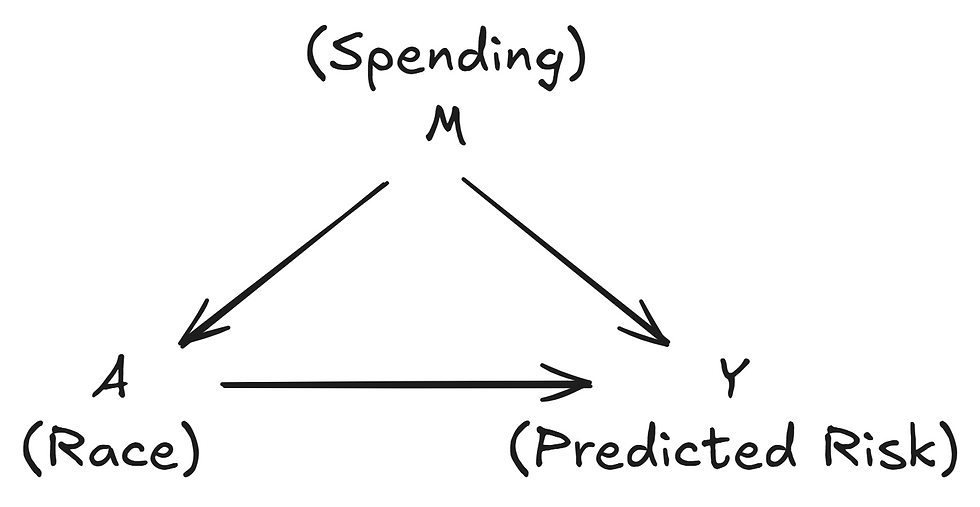

Visualising It: What is a DAG?

To keep these relationships clear, causal analysts use Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs). These are simple flow charts that show assumed causal connections between variables.

Nodes = variables (e.g., Gender, Education, Job Offer).

Edges = causal relationships.

Paths = sequences of edges from a protected attribute to an outcome.

For this example, the DAG would look like this:

The arrow A → Y shows the direct effect of race on risk.

The path A → M → Y shows the indirect effect through past spending.

A DAG makes explicit what paths you believe exist and therefore helps reason about which paths should be “blocked” to ensure fairness.

Choosing the Right Fairness Definition: It Depends

In health, defining fairness is inherently subjective. Which pathways are considered unjust depends on ethics, law, and stakeholder perspectives. On top of this, fairness depends on context: data are collected differently across healthcare systems, and even two hospitals in the same city may follow different practices. Therefore, there is no universal solution, the path could be acceptable or not depending on context.

For example, should genetic risk scores take ancestry into account? For some health conditions, ancestry captures meaningful biological variation. For others, it may simply reflect social and structural biases, risking unfair predictions. We see this in prostate cancer, where prevalence is higher among Afro Latino men due to African ancestry, and in liver cancer, where predisposition is higher among Mexican men due to indigenous background. In other contexts, however, ancestry may simply reflect social and structural biases, risking unfair predictions.

To truly promote health equity, fairness must be path-specific, context-sensitive, and informed by causal thinking.

The Take-home Message

Statistical fairness is only one piece of the puzzle, it won’t solve disparities by itself.

By asking how inequity flows through the health system, we can build predictive models and interventions that align with the real-world drivers of injustice. Path-specific fairness helps us design systems that treat patients equitably, not just equally.

If you’d like to dive deeper:

Pearl, J. (2009). Causality. A foundational text that introduces the mathematics of causal inference and its applications, aimed at researchers and advanced students.

Nabi & Shpitser (2018). Fair Inference on Outcomes. A technical paper that applies causal inference to fairness questions, most useful for academics and practitioners.

Pleko & Bareinboim (2024). Causal Fairness Analysis. A recent work that extends causal approaches to fairness, written for academics and applied data scientists interested in state-of-the-art methods for addressing bias in algorithms.

And checkout past webinars hosted by us at DSxHE!

Glossary

Direct Effect (DE)

The impact of a variable (e.g., race) on an outcome (e.g., predicted risk) that is not mediated by any other variable. It represents a straightforward cause-and-effect relationship.

Directed Acyclic Graph (DAG)

A graphical representation used in causal analysis to denote relationships between variables. In a DAG, nodes represent variables, and directed edges (arrows) indicate causal connections without any cycles (i.e., no variable can be both a cause of and a consequence of itself).

Indirect Effect (IE)

The effect of a variable on an outcome that operates through one or more intermediary variables. For instance, race may indirectly affect health outcomes through spending patterns.

Natural Direct Effect (NDE)

Quantifies the effect of a treatment or attribute on an outcome while holding other variables constant. It specifically measures how much of the impact on health risk is directly due to race when spending is fixed.

Natural Indirect Effect (NIE)

This captures the portion of the effect that travels through a mediator variable. It shows how changes in spending related to race affect health outcomes.

Comments